SCI论文:柱状水囊导管经尿道前列腺扩开术治疗良性前列腺增生症

发布时间:2017-11-27 09:24

Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Using Transurethral Split of the Prostate

with a Columnar Balloon Catheter

Using Transurethral Split of the Prostate

with a Columnar Balloon Catheter

Weiguo Huang, MM,1 Yinglu Guo, MM,2 Guofeng Xiao, BM,3 and Xiang Qin, MM3

2015年3月SCI(纽约腔镜泌尿外科杂志),第29卷,344-350页

Abstract

Transurethral dilation of the prostate (TUDP) with a spherical balloon catheter is a traditional treatment for patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). TUDP, however, has been abandoned in clinical application because of its unsatisfying treatment benefit and severe complications. In this study, we redesigned an improved TUDP surgical procedure-ransurethral split of the prostate (TUSP)-by replacing the spherical balloon with a columnar balloon. To evaluate the clinical therapeutic effect, we compared the lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) of patients with BPH after TUSP treatment and analyzed the urethra through CT films. Animal experiments were performed on aged dogs to investigate the urine function and electromyography (EMG) changes. Histopathology was used to evaluate the inflammation and injury. In addition, collagen content was detected by Trichrome Masson. TUSP attenuated LUTS and reconstructed the urethra in patients with BPH. The attenuation of LUTS was reflected in terms of LUTS parameters such as peak urine flow rate, postvoid residual urine volume, quality of life score, and International Prostate Symptom Score. TUSP expanded the urethra in experimental dogs by splitting the prostate tissues and decreasing the collagen content, with maintenance of normal urinary function and EMG characteristics. The successful clinical application of TUSP with significant therapeutic effect and limited complications made TUSP an ideal choice for the patients with BPH.

Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is associated with abnormal amplifications of epithelial and stromal cells in the prostate gland.1 With the expansion of aging populations world-wide, BPH has become an important public health problem for their induction of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), which interfere with daily activities and life quality of aging men.2 In recent decades, many surgical methods have been de-veloped for treating patients with BPH.3 So far, transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is considered to be the gold standard of treatments for patients with BPH.4 The traditional TURP procedure, however, carries out resections and leads to longer hospital stay and higher medical cost.5 Therefore, TURP management of BPH necessitates good physical status as well as good economic conditions of the patients, making its application difficult in developing countries.Burhenne and colleagues6 began animal experiments and clinical research on transurethral dilation of the prostate (TUDP) as early as 1984. Application of balloon dilation to patients with BPH was first reported in the United States in 1987 by Castaneda and coworkers.7 Because of the simple operation and less in-vasiveness, TUDP was once popular and performed worldwide.8 Further clinical research, however, showed uncertain therapeutic effect of the balloon dilation method on BPH because most patients had recurrent urethral obstruction and various compli-cations 1 year after TUDP.9 Therefore, the TUDP was gradually abandoned in the treatment of patients with BPH.In this study, we improved the TUDP by redesigning the balloon catheter and performed transurethral dilation. The improved TUDP was named transurethral split of the prostate (TUSP) because of the split of the prostate capsule during the procedure. Compared with traditional TUDP, TUSP re-placed the spherical balloon catheter with a columnar balloon catheter. We demonstrated that application of the columnar balloon catheter was effective and therapeutic in the clinical research including 113 patients with BPH. Practice of TUSP on animals also confirmed that widening the urethra with transurethral prostatic columnar balloons was safe and feasible. To investigate the mechanisms by which TUSP treated BPH, we performed histopathologic examination of prostatic tissues from experimental animals and found that TUSP expanded the urethra via tearing the prostatic tissues and decreasing the collagen content.

1Urinary Surgery, the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University, Nanjing, China.

2Urinary Surgery, the First Hospital of Peking University, Beijing, China.

3Nanjing Shuangwei Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China.

TUSP WITH COLUMNAR BALLOON CATHETER

Methods

Patients with BHP

This study enrolled 113 patients who received TUSP between March 2006 and March 2011. The patients were aged 68 to 94 years, with an average age of 74.6 years. All of the patients had lower urinary tract obstruction caused by BPH, with durations ranging from 5 to 15 years. They also had different degrees of major organ diseases, such as pulmonary insufficiency in 27 patients, high blood pressure, coronary heart disease, or cardiac insufficiency of 53 patients, diabetes in 21 patients, mild-to-moderate kidney function damage in 9 patients, cerebrovascular sequela in 3 patients, and chronic cerebral infarction in 4 pa-tients. Among the 113 patients with BPH, a diagnosis of prostate cancer was eliminated in eight patients with anal inspection and transrectal prostatic biopsy; after TURP in five patients; and after an invasive operation in one patient, who had recurrence.

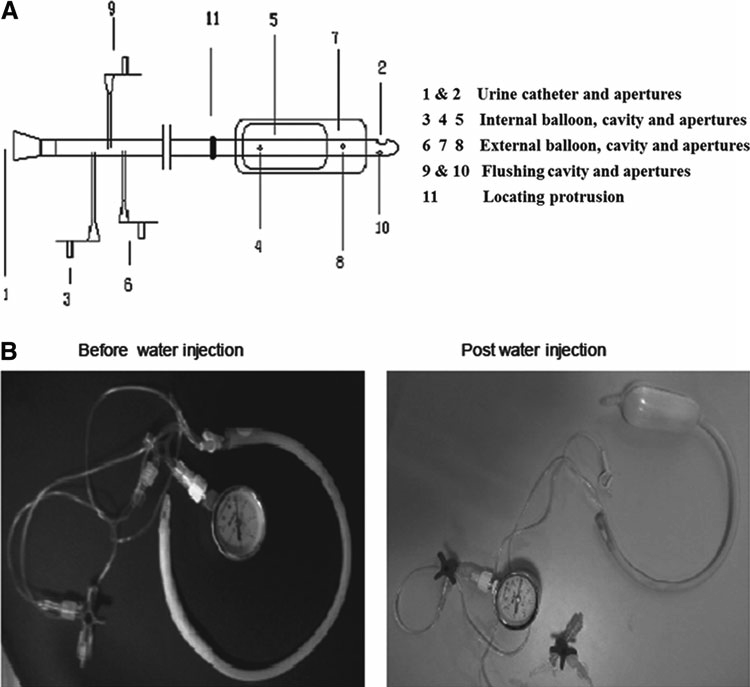

Improved columnar balloon catheter

Figure 1 shows the structure of the improved columnar balloon catheter applied in TUSP. The columnar balloon catheter comprises an internal balloon and an external bal-loon, with a maximum diameter up to 38 mm when expand-ing. During TUSP, the external balloon expanded the bladder neck and prostatic urethra while the internal balloon ex-panded the membranous urethra, both with 0.3 MPa pressure. There were different sizes of the columnar balloon catheters (balloon length ranging from 8 to 12 cm; internal diameter ranging from 3.2 to 3.8 cm); the sizes were selected according to the sizes of patients’ prostates and the length of the posterior urethras. The balloon with internal diameter of 3.2 cm and the length of 8 cm was applied for the prostate with the volume less than 40 cc, 3.5 cm and 9 cm for 40 to 60 cc, 3.6 cm and 10 cm for 60 to 80 cc, 3.7 cm and 11 cm for 80 to 100 cc, and 3.8 cm and 11 to 12 cm for larger than 100 cc.

Human surgical methods

Various sizes of transurethral catheters were chosen ac-cording to the prostate volume and bladder postvoid residual (PVR) urine volume after preoperative routine physical exam-ination and symptomatic treatment for medical complications. With low spinal anesthesia and epidural anesthesia, patients were placed in the lithotomy position followed by urethral ex-pansion using metal expander. The columnar catheter was in-serted into the bladder and then pulled out gradually.

Appropriate position of the catheter was confirmed by the breakthrough feeling when the locating protrusion was passing through the membranous external sphincter. In the proper position, the locating protrusion could be touched at the skin edge of the perineum and the internal balloon was localized in the membranous urethra. Then the internal and external balloons were expanded gradually to 0.3 MPa by injecting sterile water into the capsules.

The injection tube was closed when the internal balloon was positioned in the membranous urethra and the external balloon positioned in the prostatic urethra. The average time of this operation was about 10 minutes. Six hours after the operation, the pressure in the balloons was gradually reduced, and the catheter was removed several days (range, 3 to 5 days) later. CT films were pictured by GE Hispeed dual.

FIG. 1. Transurethral split of the prostate with columnar balloon catheter.

(A) The schematic drawing of the columnar balloon catheter.

(B) Pictures of the columnar balloon catheter before (left) and after (right) the injection of sterile water.

Experimental animals

Ten male dogs whose tooth age was 8 years were provided by the Animal Center of Peking University. All experiments involving dogs were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Peking University. The 10 male dogs were randomly divided into the TUSP group and control group, with 5 dogs per group.

Animal surgical methods

Dogs in the TUSP group were anesthetized by sodium pentothal and a lower abdominal incision was made to expose the extraperitoneal bladder and prostate. Concentric electrodes were positioned at the external urethral sphincter under the prostatic apex. The changes of bladder pressure and electromyography (EMG) during the postvoiding process after bladder instillation were recorded using the BIOPAC multichannel EMG recorder. A 2% lidocaine gel was squeezed into the urethra to prevent urethrospasm. The columnar balloon catheter was used to expand the bladder neck prostatic urethra, and membranous urethra for 5 minutes with a pressure of 0.3 MPa. Then the pressure was reduced to 0.1 MPa, and the balloon in the membranous urethra was forced into the posterior urethra for 24 hours. Finally, the

columnar catheter with no pressure was set as the urinary catheter for a week.Examinations were performed 1 week after the expanding.Both bladder pressure and EMG were detected before the animals were sacrificed. The dogs in the control group did not receive any surgical procedure. The detailed surgical process

and analysis in the control group and TUSP group are shown in Table 1.

Function and pathologic analysis

Cystoscopy, leak point pressure measurement, and EMG measurement were performed on the experimental dogs both before the surgery and before their sacrifices. The diameter of the prostatic urethra (1 cm above the colliculus seminalis) was detected after the dogs were sacrificed. The bladder neck, prostatic urethra, membranous urethra, and urethral sphincter were collected from sacrificed dogs for hematoxylin and eosin staining. Trichrome Masson was performed to detect the difference of collagen content between the expanding group and the control group. Statistical analysis All data were expressed as the mean – standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using Biostatistics ver.3 software. The t tests were used to calculate the P values.Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Table 1. Surgical Process and Analysis in Dogs Divided into Control Group and Transurethral Split of the Prostate Group

Control group TUSP group

Expanding sites None Bladder neck、Prostatic urethra、Membranous urethra

High pressure expansion None 0.3 MPa, 5 minut s

Low pressure expansion None 0.1 MPa, 24 hours

Catheter retention None 0 Pa, 1 week

Analysis Cystoscopy Leak point pressure EMG Histopathology

TUSP = transurethral split of the prostate;EMG= electromyography.

Results

TUSP attenuated LUTS and reconstructed urethra in patients with BPH

A total of 113 patients with BPH with an average prostate volume of 46.8 -9.2 cc, which was detected by transrectal ultrasonography, were included in the study. The mean peak urine flow rate (Qmax), PVR, baseline quality of life (QoL) score and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) were 7.4 -1.6 mL/s, 78 -10.2 mL, 4.8-0.2, and 21.6-4.4, re-spectively, in patients with BPH before surgery. The mean prostate-specific antigen level ranged from 0.8 ng/mL to 18.6 ng/mL. All patients received transurethral dilation with a columnar balloon catheter, and the average operative time was 10 minutes.

Patients were followed up for 3 to 24 months after surgery. Qmax, PVR, QoL score, and IPSS were determined at each visit. The mean Qmax was increased to 15.8-2.1 mL/s while the mean PVR decreased into 22 -8.1 mL after the proce-dure. The significant elevation of Qmax and reduction of PVR indicated the recovered LUTS in patients with BPH after TUSP. The mean QOL score and IPSS was reduced to 1.4 -0.3 and 6.8 -1.2, respectively. The characteristics of patients with BPH before and after transurethral dilation are shown in Table 2. Significant improvements in terms of Qmax, PVR, QoL, and IPSS were observed after TUSP.

After TUSP, five patients had stress urinary incontinence; however, the symptom disappeared within 2 days. Until August 2011, the longest follow-up duration for the patients after TUSP lasted up to 5 years. Only two patients had re-current urethral obstruction at 3 years after operation because of an inaccurate positioning and an incorrect selection of catheter size. Until September 2014, 99 patients were suc-cessfully followed up and the follow-up duration ranged from 38 to 98 months. The symptoms of the two patients were

Table 2. Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms of Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Before and After Transurethral Split of the Prostate

| Indicators | Before TUSP | Post-TUSP | P value |

| Qmax (mL/s) | 7.4±1.6 | 15.8±2.1 | < 0.001 |

| PVR (mL) | 78±10.2 | 22±8.1 | < 0.001 |

| QoL | 4.8±0.2 | 1.4±0.3 | < 0.001 |

| IPSS | 21.6±4.4 | 6.8±1.2 | < 0.001 |

Data presented as mean ?standard deviation.

TUSP = transurethral split of the prostate; Qmax = maximal urinary flow rate; PVR = postvoid residual; QoL = quality of life; IPSS = International Prostate Symptom Score.

FIG. 2. Transurethral split of the prostate (TUSP) reconstructs the urethra in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

(A) Representative CT film of the prostate and urethra in patients before TUSP.

(B) Representative CT film of the prostate and urethra in patients shortly after TUSP.

(C) Representative CT film of the prostate and urethra in patients. The arrows indicate the urethra. improved after the second TUSP procedure. Besides, no other patient reported dysuria until the end of the follow-up time.

Medical CT films were used to analyze anatomic and im-age parameters of the urethra. As shown in Figure 2, the prostate tissue pressed the urethra and the urethral lumen was invisible before TUSP. Shortly after the TUSP procedure, the balloon expanded the posterior urethra. The anterior fi-bromuscular stroma and prostate capsule were split to both the sides, leading to decompression of the prostatic urethra. After recovery, CT films showed that most of the prostate tissue closed again but at the top joint part, a crater-like hole remained where the urethra was reconstructed.

FIG. 3. Transurethral split of the prostate (TUSP) expands the urethra in dogs with benign prostatic hyperplasia while maintaining normal leak point pressure and electromyography (EMG).

(A) Representative photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained prostate from aged male dogs with BPH.

(B) Representative photomicrographs of H&E-stained prostate capsule (black arrow) and urethra (hollow arrow) after TUSP.

(C) Statistical analysis of the urethral diameters in the control group and TUSP expanding group (n = 5 dogs/group; mean -standard deviation; P < 0.01).

(D) Statistical analysis of the leak point pressure in the control group and TUSP group before and after TUSP (n = 5 dogs / group; mean -standard deviation).

(E) Representative EMG of urethral sphincter before (upper row) and after (bottom row) TUSP.

TUSP surgery expanded the urethra in dogs with BPH with the maintenance of normal urinary function and EMG characteristics

We then investigated the therapeutic effect of TUSP on BPH on aged dogs. Histology showed the aged male dogs had BPH under normal states (Fig. 3A). After TUSP, the prostate capsule was split and the urethra was expanded significantly (Fig. 3B). The prostatic urethra diameter increased significantly after TUSP, indicating the TUSP induced expansion of the prostatic urethra (Fig. 3C). Because TURP might cause complications such as urine leakage,10 changes of urodynamics and EMG were accessed after TUSP.11,12 The leak point pressures in the ex-panding group before and after TUSP were comparable and showed no significant difference when compared with the con-trol group (Fig. 3D). Analysis on EMG of the urethral sphincter in live dogs showed that the urethral sphincter displayed inter-mittent high tension EMG activities during urine storage and low tension resting potential during micturition (Fig. 3E).

The EMG of the urethral sphincter after TUSP was similar to that before TUSP, although the frequency and amplitude of EMG after TUSP were slightly higher. Therefore, the TUSP surgery expanded the urethra while maintaining the normal urinary function and EMG characteristics.

TUSP induced inflammation and decreased collagen contents

To further investigate the mechanisms involved in the therapy of BPH, sections were prepared from prostatic tissues of experimental dogs. Histology analysis (Fig. 4A) showed inflammation, bleeding, and necrosis at the prostatic urethra, prostatic stroma, bladder neck, and membranous urethra. Mucosa shed in the prostatic urethra, bladder neck, and membranous urethra. Necrosis and denaturation of smooth muscle were observed at the prostatic stroma and membra-nous urethra. Fibers in the prostate capsule bled.

We also detected the content of collagen that played an im-portant role in BPH. Consistent with previous studies in mice demonstrating the collagen was abundant in the aging prostate,13 we found collagen was abundant in the bladder neck, prostatic urethra, and urethral stroma of control dogs (Fig. 4B, upper row). The content of collagen, however, was much less in the bladder neck, prostatic urethra, and urethral stroma of expanding dogs after TUSP (Fig. 4B, bottom row). Thus, we suspect the expan-sion of the urethra may be an integrated effect of multiple factors.

TUSP induced urethral inflammation, denaturation of smooth muscle fibers, and decreased production of collagen, all of which impaired the contractility of prostatic tissues. Peripheral tissues then filled the dehiscence of the prostate capsule, excluding the retraction of prostatic stroma that led to the expansion of the urethra.

FIG. 4. Transurethral split of the prostate (TUSP) induces prostate injury and decreases collagen content in

dogs with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

(A) Representative photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosinstained prostatic urethra (upper left), prostatic stroma (upper middle), prostate capsule (upper right), bladder neck (bottom left), membranous urethra (bottom middle) in dogs after TUSP, and prostate without TUSP (bottom right).

(B) Representative photomicrographs of Trichrome Masson stained bladder neck (left), prostate (middle) and urethral stroma (right) from control dogs (upper row) and dogs after TUSP (bottom row).

Discussion

Aged men usually have BPH and secondary LUTS, which seriously decrease their life quality.2 TUDP used to be a popular treatment for patients with BPH patients but was fi-nally abandoned because of its invalid therapeutic effect.9 In this study, we designed a new catheter by changing the shape of the balloon from a sphere into a column and performed TUSP. The clinical trials showed enormous advantages of TUSP treatment for patients with BPH.The parameters of LUTS such as the mean Qmax,the mean PVR,QoL score,

and the mean IPSS all returned to normal levels after TUSP. TUSP constructed the urethra in patients with BPH. Previous study showed a clear correlation between prostatic occlusion of the urethra and the presence of a middle lobe14; whether the existence of a middle lobe will affect the therapeutic effect of TUSP is unknown and needs further investigation.

Animal experiments also demonstrated that TUSP expanded the urethra with normal urinary function and EMG characteristics. Both prostate capsule disruption and collagen reduction occurred after TUSP. Because of the defect of CT, however, we are unable to conclude which process happened anteriorly and the causality between the two processes. We suspect that both processes contribute to preventing the folding of prostate tissues and its capsule to maintain a long-term patulous urethra. Although the current opinion on the gold standard and primary surgical procedure for patients with BPH is TURP during which resection is necessary,15 the high fee, large wound areas, special instruments, and following complications limit the application of TURP, especially in developing countries.16

Our research on TUSP demonstrated BPH-caused LUTS could be cured without excising the gland. The point to treat BPH-causedLUTS iswhether the urethra is expedited or not.The columnar balloon catheter inTUSP consists of an internal balloon to expand the bladder neck and prostatic urethra, and an external balloon to expand the urethral sphincter. As long as the obstructive parts are expanded or released, dysuria problems might be resolved. In addition, the prostate capsule was split at the top joint part of the prostate during the operation,whichmay prevent the recurrence of BPH. Therefore, the highlight of the TUSP technique is: It treated theLUTS caused byBPHthrough splitting the prostate capsule and expanding the urethra, which not only avoided resection but also showed significant curative effect.

We have performed the TUSP procedure on animals and in clinical practice since 2006, and the TUSP technique has matured to be a safe operation without causing voiding dysfunction. The key to a successful TUSP is choosing the correct size and accurate positioning of transurethral catheters.Two patients had recurrent urethral obstruction at 3 years after operation, whichmight suggest that it was beneficial for patients to receive CT detection of the prostate and urethra during 3 to 4 years after TUSP. The remaining balloon after expansion and gradually reduced pressure benefited hemostasis. The catheter was retained in the urethra without pressure for urinary catheterization, which prevented urine leakage. Furthermore, TUSP breaks the penalty field of touching the membranous urethra without damaging nerves and the urethral sphincter.

EMG represents the electrical activity of prostatic muscle and is associated with the dynamic component of patients with symptomatic BPH.17 In our study, EMG reveals a normal myoelectric activity of the urethral sphincter after an appropriate expansion of the obstructive part at the urethral membrane by TUSP, which proves that TUSP may not induce trauma of the urethral sphincter or long-term incontinence,but plays a crucial role in sustaining normal urinary function. The minimal hurt on patients’ physiology and psychology could prolong a longer average life expectancy for elderly men and is a huge advantage of TUSP.

Conclusion

TUSP fills in the blanks of solving urethral obstructive problems without scalpels. This technique produced minimal trauma, short operative time, and high safety coefficient. TUSP is an ideal choice for patients who are infirm, intolerant , or indisposed to resection.

Disclosure Statement:No competing financial interests exist.

References

1. Kulig K, Malawska B. Trends in the development of new drugs for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr Med Chem 2006;13:3395-3416.

2. Roehrborn CG. Current medical therapies for men with lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia:Achievements and limitations. Rev Urol 2008;10:14-25.

3. Biester K, Skipka G, Jahn R, et al. Systematic review of surgical treatments for benign prostatic hyperplasia and presentation of an approach to investigate therapeutic equivalence (non-inferiority). BJU Int 2012;109:722-730.

4. Pinheiro LC, Martins Pisco J. Treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2012;15:256-260.

5. Andersson KE. Treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms:Agents for intraprostatic injection. Scand JUrol 2013;47:83-90.

6. Burhenne HJ, Chisholm RJ, Quenville NF. Prostatic hyperplasia:Radiological intervention. Work in progress.Radiology 1984;152:655-657.

7. Castaneda F, Letourneau JG, Reddy P, et al. Alternative treatment of prostatic urethral obstruction secondary to benign prostatic hypertrophy. Non-surgical balloon catheter prostatic dilatation. Rofo 1987;147:426-429.

8. Wasserman NF, Reddy PK, Zhang G, Berg PA. Experimental treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia with transurethral balloon dilation of the prostate: Preliminary study in 73 humans. Radiology 1990;177:485-494.

9. Vale JA, Miller PD, Kirby RS. Balloon dilatation of the prostate-hould it have a place in the urologist’s armamentarium? J R Soc Med 1993;86:83-86.

10. Losco G, Mark S, Jowitt S. Transurethral prostate resection for urinary retention: Does age affect outcome? ANZ J Surg 2013;83:243-245.

11. Nitti VW, Kim Y, Combs AJ. Voiding dysfunction following transurethral resection of the prostate: Symptoms and urodynamic findings. J Urol 1997;157:600-603.

12. Bianchi F, Cursi M, Ferrari M, et al. Quantitative EMG of external urethral sphincter in neurologically healthy men with prostate pathology. Muscle Nerve 2014;50:571-576.

13. Bianchi-Frias D, Vakar-Lopez F, Coleman IM, et al. The effects of aging on the molecular and cellular composition of the prostate microenvironment. PloS One 2010;5.

14. el Din KE, de Wildt MJ, Rosier PF, et al. The correlation between urodynamic and cystoscopic findings in elderly men with voiding complaints. J Urol 1996;155:1018-1022.

15. Li X, Pan JH, Liu QG, et al. Selective transurethral resection of the prostate combined with transurethral incision of the bladder neck for bladder outlet obstruction in patients with small volume benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH): A prospective randomized study. PloS One 2013;8:e63227.

16. Bisonni RS, Lawler FH, Holtgrave DR. Transurethral prostatectomy versus transurethral dilatation of the prostatic urethra for benign prostatic hyperplasia: A cost-utility analysis. Fam Pract Res J 1993;13:25-36.

17. Sahiner T, Atahan O, Aybek Z. Prostate electromyography:A new concept. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 2000;40:103-107.

Address correspondence to

Weiguo Huang, MM Urinary Surgery The Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University No. 321 Zhongshan Road Nanjing 210008 China.

E-mail: weiguohuangwgh@163.com

Abbreviations Used

BPH=benign prostatic hyperplasia;

EMG=electromyography;

IPSS=International Prostate Symptom Score

LUTS=lower urinary tract symptoms;

PVR=postvoid residual;

Qmax=peak urine flow rate;

QoL=quality of life

TUDP=transurethral dilation of the prostate;

TURP=transurethral resection of the prostate

USP=transurethral split of the prostate

DOI: 10.1089/end.2014.0825

Editorial Comment for Huang et al.

Pat Fulgham, MD

The authors have conducted a study to evaluate the mechanism and effectiveness of transurethral balloon dilation of the prostate for the management of bladder outlet obstruction. The patients selected had moderate to significant obstructive voiding symptoms, had moderately enlarged prostates (average 48 cc), and underwent a single session of transurethral balloon dilation of the prostate.

The patients appeared to have good outcomes based on preoperative and postoperative evaluation of their quality of life and International Prostate Symptom Score scores, and the results were relatively durable. CT scans in some patients confirmed anterior disruption of the prostate with resultant sustained defect anteriorly in some.

The authors conclude that the use of a columnar balloon is superior to the use of a spherical balloon in achieving this clinical outcome; however, there are no direct comparisons in this patient population between the use of a spherical balloon and the use of a columnar balloon. Review of the literature from the 1980s and 1990s, when transurethral balloon dilation of the prostate was introduced and in relatively widespread use, showed conflicting but generally disappointing results in terms of the durability of clinical outcomes.1? Areview of theliterature reveals that balloons similar to the one described in this study were in use at that time.3,4 It is possible that the differentiating aspect of the procedure described in this study was that the

balloon was left fully inflated for 5 to 6 hours after the procedure. It is possible that this expansion and compression of the prostate could lead to some vascular compromise of the tissue and perhaps result in more scar tissue formation and decreased collagen deposition as well as some atrophy of the glandular tissue itself. If the proposed mechanism of action is correct, very similar results could theoretically be obtained by simple transurethral incision of the prostate and capsule anteriorly.

References

1. Vale JA, Miller PD, Kirby RS. Balloon dilatation of the prostate-should it have a place in the urologist’s armamentarium? J R Soc Med 1993;86:83-86.

2. Chiou RK, Binard JE, Ebersole ME, et al. Randomized comparison of balloon dilation and transurethral incision for treatment of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Endourol 1994;8:221-224.

3. Moseley WG. Balloon dilatation of prostate: Keys to sustained favorable results. Urology 1992;39:314-318.

4. McLoughlin J, Keane PF, Jager R, et al. Dilatation of the prostatic urethra with 35mm balloon. Br J Urol 1991;67:177-181.

Address correspondence to:

Pat Fulgham, MD Oncology Services Texas Health Presbyterian Dallas 8210 Walnut Hill Lane, Suite 014 Dallas, TX 75231

E-mail: pfulgham@gmail.com